In the early days of the 17th Century a ship left the home shores of England bound for the new world. The passengers were families escaping religious persecution in England and seeking a better life far away in another country.

The settlers arrived on the north east cost of America and set up their camp next to the Merrimack River in what is now north-eastern Massachusetts. This was originally called ‘Pentucket’ by the native Indians, a word meaning ‘Land of the Winding River’, which describes its location perfectly succinctly. The settlers eventually changed the name to ‘Haverhill’ in honour of the English birthplace of their leader, John Ward.

Native American activity along the Merrimack River prior to European settlement was intense, with several tribes known to have been in the Haverhill area, including the Pentuckets, Pawtuckets and Agawams.

The Indians could not come to terms with the settlers’ alien form of land use, and this was always going to be a bone of contention. Having said that, regular contact between the Pennacook and early English settlers took place from 1620 onwards, and the early encounters were generally friendly.

This situation, however, would change

with time, when the ‘foreigners’ became more suspicious (often mistakenly)

of the natives’ activities.

In its earlier years this frontier

town suffered severely from the forays of the Indians, and in 1690 the

abandonment of the settlement was contemplated. It was attacked

by Indians on March 15, 1697, when about 39 people were either killed

or captured, and about 6 houses were burned. Some of these victims are

buried in Pentucket Cemetery, which was consecrated in 1668.

The

History of Haverhill Massachusetts .....

A Life Feature by Ian Hornsey

Did you know that Haverhill Suffolk

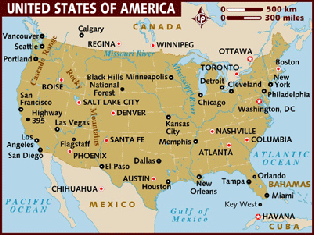

is not the only town by that name. There is another Haverhill in USA in

the state of Massachusetts (MA).

The American Haverhill was founded in

the 17th century by pilgrims from England (including an ancestor of Jodie

Kidd the Strictly Come Dancing star).

Since it was founded Haverhill MA has

grown rapidly and now has three times the population of our own town (60,000

people). Haverhill MA is a modern successful

city with major links to the rest of America and is considered a gateway

city for global technology and commerce.

Haverhill started as a farming community,

and then gradually developed into an industrial centre, commencing with

gristmills and sawmills, which were worked by readily-

As with most towns and villages, it was

the topography of the land that was to shape Haverhill’s history. The

surrounding terrain is of rolling hills (the highest being just over 300’)

which are strung along the Merrimack River at the eastern edge of town.

These hills form a semi-circular ring around

the downtown area. Between the hills lie long, narrow valleys carrying

the creeks and rivers that provided, fish, and water-

Nestling amongst the highest of Haverhill’s

hills are three freshwater lakes: Kenoza, Saltonstall, and Round Pond,

and it is these that probably determined the positioning of the first

settlement immediately to the south. Across the river is a fourth lake,

Chadwick’s Pond, and all four bodies of water are relics of ancient receding

glaciers. The north-west quarter of the

city, known as Ayer’s Village, is the only part that has a generally flat

topography.

Staue of Hannah Dunston

As might be expected, there are many

tales of derring-

They were marched for fifteen days

in the freezing March weather. During this time, the Indians took

the baby from Hannah and killed her by smashing her against a tree.

The grieving Hannah and Mary then travelled

further north with a family group and their Indian captors, during which

time they were joined by Samuel Lennardson, a 14-year-

One night, when their captors were asleep, Hannah,

Mary and Samuel attacked them with their own tomahawks, and killed ten

out of the twelve of them only a young boy and a woman managed to escape.

Their territory extended through the Merrimack River valley of southern and central New Hampshire, including parts of north-eastern Massachusetts. Pennacook is derived from the Abenaki word ‘penakuk’, which translates as ‘at the bottom of the hill’. Originally, there may have been as many as 12,000 Pennacook indians and 30 villages in this area, but many of the natives perished from smallpox just prior to English settlement. Smallpox began along the Merrimack River in 1631 and spread into a major epidemic in New England during the years 1633-35. The disease returned in 1639, and was followed by influenza in 1647, smallpox 1649-50, and diphtheria in 1659. By the end of the 1670s, the indigenous population had declined from 2,500 to around 600.

One of the major problems facing the early settlers was to do with lifestyle. The Europeans were essentially farmers, and took their livestock, and some of their crops, with them. Rearing animals, in particular, necessitated the partitioning off of parcels of land – something that the Indians, who were basically hunters, had never done. The natives did grow a few crops; maize, beans and squash being the main ones that were planted in small patches. Their hunting was done mainly in the winter months, with deer, bear, elk and small animals being the main targets. Fishing was carried out all year round, and wild foods (berries, etc.) were also gathered.

Taking the ten scalps with them, the refugees appropriated a canoe, and, using the darkness of night as a cover, made their way back down the river to Haverhill. On receipt of the scalps, the Massachusetts General Court rewarded them for killing the raiders; Hannah receiving £25 and the other two sharing the same sum between them.

The exploit became renowned, partly due to an account in ‘The Ecclesiastical History of New England’, a book written by Cotton Mather in 1702, which details the religious development of Massachusetts and other nearby colonies in New England from 1620 to 1698. Hannah became even more celebrated during the 19th century as her story was retold in many genealogical histories.

In 1879 a bronze statue of her grasping

a tomahawk was placed in Haverhill town square (now GAR Park), where it

still stands,.

Some of her artifacts are displayed at

the Haverhill Historical Society, which is located in the Buttonwoods

Museum, Water Street.

A Garrisson House, which would have been used as a defensive retreat when the town was attacked by Indians.